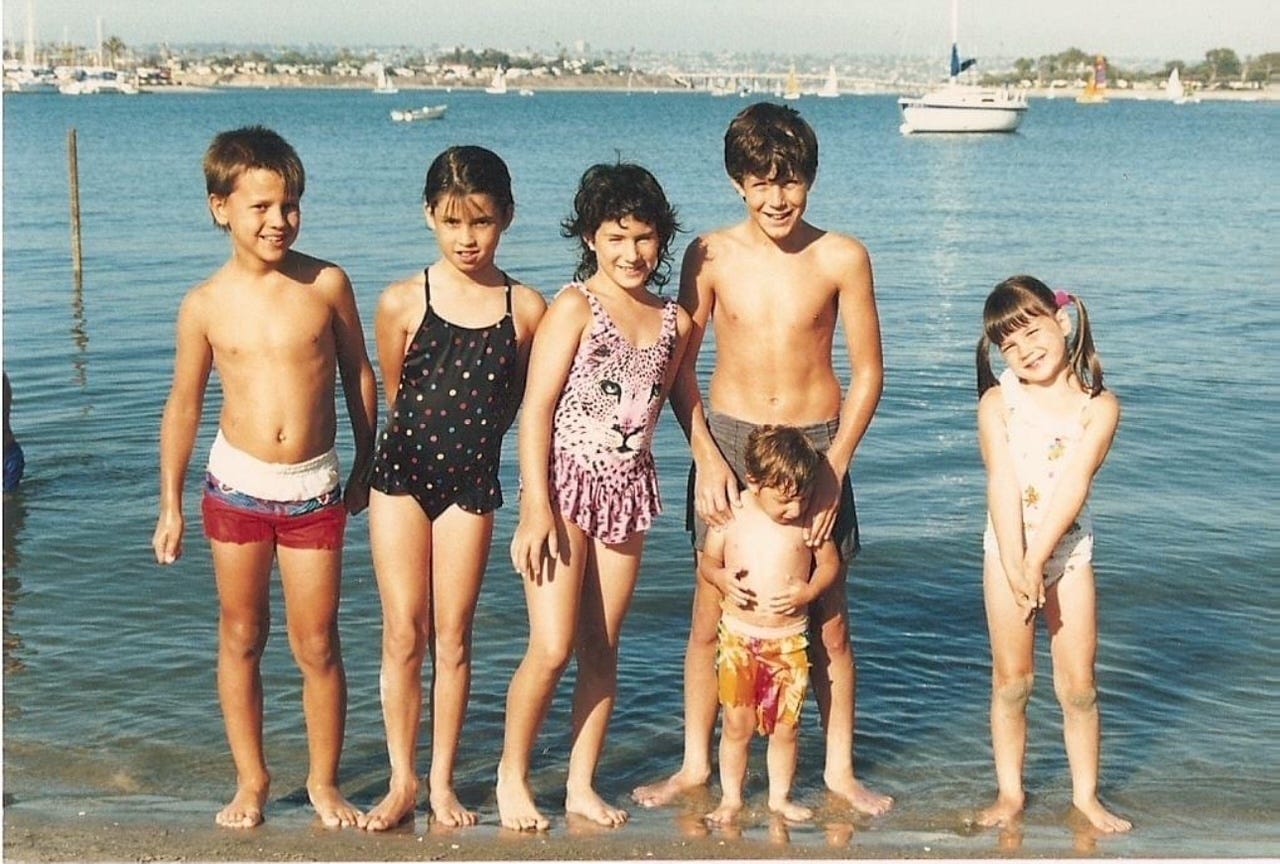

When I was young, the best party of the summer was at Dr. Bark’s. He was my dad’s boss, and hoste…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Piecemaker: Musings of a Midwest Maker to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.